PRODUCT LAUNCH

Overlooked no more: celebrating the life and work of Alan Turing

The Bank of England has issued a new £50 note featuring Alan Turing ‘to celebrate his achievements and the values he symbolises’. Mohamed Dabo looks at the life and work of one of the UK’s most important scientists

A

lan Turing was a brilliant mathematician and logician, who almost single-handedly cracked the German Enigma machine and changed the course of World War II, while giving birth to the computing age.

During his lifetime, his historic achievements went unrecognised. Instead, he was publicly disgraced for being a gay man in a time when homosexual acts were illegal.

Today, the maverick genius is acknowledged to have two formidable achievements – apart from his role in the Enigma code-breaking enterprise at Bletchley Park: the theoretical construct now known as the Turing Machine, which is now taught to all computer science undergraduates in a Theory of Computation class; and the development of the theory of artificial intelligence in his famous paper, Computing Machinery and Intelligence.

Early years

Alan Mathison Turing was born on 23 June 1912 in London, and died on 7 June 1954 in Wilmslow, Cheshire. He was not only a mathematician and logician, but also a computer scientist, cryptanalyst, philosopher and theoretical biologist.

He graduated at King's College Cambridge, with a degree in mathematics. He subsequently moved to Princeton University to study for a PhD in mathematical logic, which he completed in 1938.

Turing was already working part-time for the UK government’s Code and Cypher School before World War II broke out.

In 1939, he took up a full-time role at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, where top-secret work was carried out to decipher the military codes used by Germany and its allies.

Cracking the Enigma code

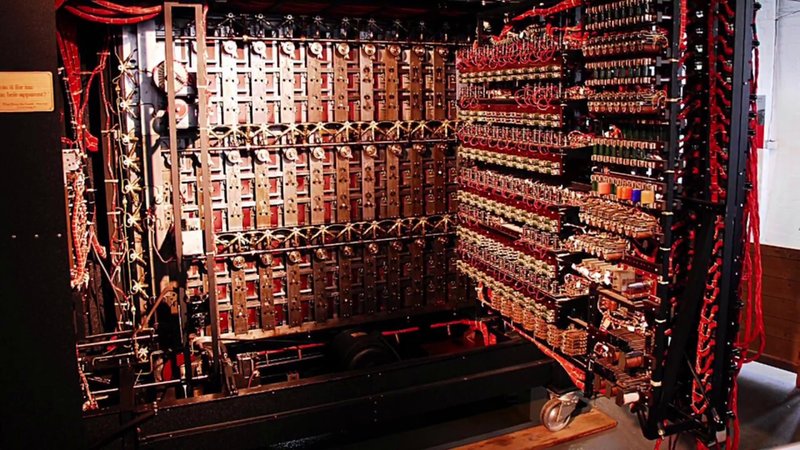

The focus of Turing’s work at Bletchley was cracking the Enigma code. The Enigma was a type of enciphering machine used by the German armed forces to send messages securely.

Although Polish mathematicians had worked out how to read Enigma messages, and had shared this information with the British, the Germans increased its security at the outbreak of the war by changing the cipher system daily.

This made the task of understanding the code even more difficult. Turing played a key role in this, inventing – along with fellow code-breaker Gordon Welchman – a machine known as the Bombe.

This device helped to significantly reduce the work of the code-breakers. From mid-1940, German Air Force signals were being read at Bletchley and the intelligence gained from them was helping the war effort.

A pivotal role

Turing also worked to decrypt the more complex German naval communications that had defeated many others at Bletchley. German U-boats were inflicting heavy losses on Allied shipping and the need to understand their signals was crucial.

With the help of captured Enigma material, and Turing’s work in developing a technique he called Banburismus, the naval Enigma messages were able to be read from 1941.

He headed the Hut 8 team at Bletchley, which carried out cryptanalysis of all German naval signals. This meant that – apart from during a period in 1942 when the code became unreadable – Allied convoys could be directed away from the U-boat 'wolf-packs'.

Turing’s role was pivotal in helping the Allies during the Battle of the Atlantic.

The Turingery technique

In July 1942, Turing developed a complex code-breaking technique he named Turingery. This method fed into work by others at Bletchley in understanding the Lorenz cipher machine.

Lorenz enciphered German strategic messages of high importance: the ability of Bletchley to read these contributed greatly to the Allied war effort.

Turing travelled to the US in December 1942 to advise US military intelligence in the use of Bombe machines and to share his knowledge of Enigma. While there, he also saw the latest US progress on a top-secret speech-enciphering system.

Turing returned to Bletchley in March 1943, where he continued his work in cryptanalysis. Later in the war, he developed a speech scrambling device which he named Delilah. In 1945, Turing was awarded an OBE for his wartime work.

The Universal Turing Machine

In 1936, Turing had invented a hypothetical computing device that came to be known as the Universal Turing Machine. After World War II ended, he continued his research in this area, building on his earlier work and incorporating all he had learned during the war.

While working for the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in Teddington, Middlesex, Turing published a design for the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE), which was arguably the forerunner to the modern computer. The ACE project was not taken forward, however, and he later left the NPL.

Turing’s enduring legacy

In 1952 Turing was arrested for homosexuality, which was then illegal in the UK. He was found guilty of gross indecency – the conviction was overturned in 2013 – but avoided a prison sentence by accepting chemical castration.

In 1954, he was found dead from cyanide poisoning; an inquest ruled the cause as suicide.

The legacy of Turing’s life and work did not fully come to light until long after his death.

Turing was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer science, providing a formalisation of the concepts of algorithm and computation with the Turing machine, which is now seen as a model of a general-purpose computer.

His impact on computer science has been widely acknowledged: the annual Turing Award has been the highest accolade in its industry since 1966.

Turing is considered to be the father of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence.

The work of Bletchley Park – and Turing’s role there – was kept secret until the 1970s, and the full story was not known until the 1990s.

It has been estimated that the efforts of Turing and his fellow code-breakers shortened the war by several years. What is certain is that they saved countless lives and helped to determine the course and outcome of the conflict.

‘A landmark moment’

Jeremy Fleming, director of the UK’s Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), says: “Alan Turing’s appearance on the £50 note is a landmark moment in our history.

“Not only is it a celebration of his scientific genius, which helped to shorten the war and influence the technology we still use today, it also confirms his status as one of the most iconic LGBT+ figures in the world.

“Turing was embraced for his brilliance and persecuted for being gay. His legacy is a reminder of the value of embracing all aspects of diversity, but also the work we still need to do to become truly inclusive.”

The Turing £50 note. Source: Bank of England